- Home

- McLay, Craig

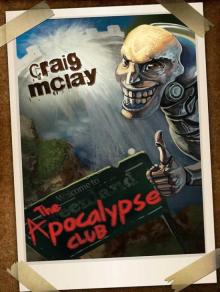

The Apocalypse Club

The Apocalypse Club Read online

The Apocalypse Club

By Craig McLay

Copyright © 2014 Craig McLay

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living, dead, or undead, is purely coincidental. All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the author or publisher.

Edition: September 2014

Nullius in verba

Contents

PART I

PART II

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18

PART III

19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27

28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

PART I

The Collected Letters of

Lord Tristan Smythe, FRS

21st June 1921

Jobrek Encampment, Tarsus

Dearest Pip,

As you know, I have no great philosophy of life and human existence, but I have been thinking much on the matter as our work here progresses. The heat is damnably oppressive and so we have been doing much of our excavation work at night, under the full moon when it is available and smoke-belching oil lamps when it is not.

Trying to sleep in the tents during the day is as easy as drifting off peacefully in the blast room of a foundry. How the Hittites ever decided to settle here is a mystery almost as obscure as the one I am here to investigate. I don’t suppose I have managed more than ten dolorous minutes of rest in the last three days. It has left my mind in a torpid and philosophical state, so please forgive me if I proceed to ramble incoherently.

You know me well enough to know that, despite all of the Reverend Kirkwood’s attempts to the contrary, I have never succumbed to the notion that there is some great and omnipotent, Zeus-resembling sky father on the other side of the clouds looking down on all of us at once. I believe in what I can see, hear, touch and study. That’s father’s influence, I suppose. He never subscribed to what he called “all that superstitious hoodle-oo” either. You have always followed mother’s example in these matters, although I suspect you did so more grudgingly than you let on.

Based on observation and my own experimentation, I have come to believe that most humans do not know why we are here (if indeed there needs to be a reason, which I do not believe is necessary), where we have come from or where we might be going. We are terrified by the fact that our lives will, eventually, end, and more terrified still by the possibility that they may end at any moment. That end may come quickly or after a great deal of suffering and pain. When we grow older and have children, we are paralyzed by the fact that such things can and will happen to them, too. Lives are small specks of light floating in an infinite darkness that will someday claim us all forever.

Or so I thought.

After Fatima and James, I fell into deep melancholy, spending days and weeks brooding over such ideas. Our recent discoveries, however, have done much to change my mind on the matter. Not on Judeo-Christian points, but an altogether different explanation.

The world is not at all what we perceive it to be.

The span of that chasm has only become clearer to me as our work here has progressed. Sorry that I cannot provide you with more detail, Pip, but our position here is tenuous and I cannot risk the possibility that this letter may come to someone other than yourself. There are many out there who will seek to discredit me (particularly Haliburton, who has been waging an active campaign practically since our project was first presented for funding) and I cannot provide them with any possible foundation for their arguments until mine has bedrock of its own. The strands are coming together, but if I grasp at them prematurely, they will dissolve in my hand like cobwebs. They will say I am driven by mania, by grief, by ego and even by glory. Perhaps, in small respects, they have a point. All of those things are tiny components in the overwhelming drive for human immortality, and they will see how foolish they were when I reveal my discovery to the world.

Only four days to go before we pack up camp to head for the sea and Alexandria. It will be wonderful to see the old city again, but I confess I am more excited about some respite from the heat. As things stand right now, I would happily sell all of my discoveries to the first merchant who can provide me with a handful of ice. Give my love to Elspeth and keep some for yourself.

Love,

T

∅

2nd November 1922

The Royal Edward Hotel, London

Dearest Pip,

Conrad Haliburton is a tit.

Do forgive my verbiage, dearest sister, but it has been nearly a fortnight since he so vilely defamed me on the very steps of Burlington House that father all but paid for and still my hands shake in their efforts to contain the furious torrent of abuse I longed to hurl into his blotchy cushion of a face. The man calls himself a scientist, but has, to my knowledge, done nothing of note in his time as chair but name a dung beetle after himself, and I say that a more appropriate legacy I would be very hard pressed indeed to wish.

You remember him, I should think. The coprophagous toad once putrefied the air of the drawing room of our own Canticle House, no doubt in a fruitless attempt to cajole father into underwriting another one of his wretched bug catching expeditions in Patagonia. Father naturally sent him packing without a shilling, which lanced that swollen boil of an ego as righteously as old St. George himself. He scurried back to his black, fly-spotted web to tend his pride and leak his poisonous pus on our family name at every opportunity.

Now that father has passed and I have become master of accounts, it seems, he feels suddenly brave enough to creep out of his bug hole and say these things in public. The man is a pestilence! I would wager he has been pricked too many times by his poisonous charges and the rot has eaten away at whatever vestiges of cognitive decorum may have remained in that gangrenous melon he carries around on his shoulders.

I will not insult your ears (and I trust you are not reciting this letter aloud to mama – at least, not without some prudent excisions! – for her temperament is more fragile now that father is not there to mollify her grander fantasies) by repeating any of what the fat, old squid had to say. Suffice it that he does not believe there is any merit to be found in our little expedition. What does he know of such things? I squash more grand discoveries under my boot heel in an afternoon than he has made in his miserable career. “Fantasists,” he called us! “Glory-seeking neophytes!” “Charlatans!” “Pursuers of mythical nonsense.”

And worse.

Had I not been so disturbed and had my wits and a notepad with me, I would have copied down some of his more outrageous statements and dispatched them immediately in a letter to old Carstairs to see if I might be able to take recourse of a more legal nature. I would enjoy nothing more than to exact my own pound of flesh (or a few hundred pounds – ha!) in recompense from that horrid parasite! Alas, I had left my case and briefing papers inside.

But enough of my complaints, which are minor and entirely rooted in the jealous bile ducts of the men I once thought of as my scientific compatriots. How are things in dreary old Sussex? I trust that the miserable weather has not inflamed your sensitive lungs. You have enough to worry about chasing after mad old mama without having to deal with another horrid bout of pneumonic coughing. I know father trusted Fotheringham with his life (and look where that got him – straight to the end of it), but I have never been entirely comfortable around the man. He still talks of ba

lancing the humours and fleeing miasmas as if all the advances of 20th century medicine were the fickle whims of a feverish schoolboy. Does he still carry that old black bag with the faded brown stripes up the side? The one with the outside pocket especially designed to hold the small jar of leeches? His “thirsty little assistants,” he used to call them. I have no doubt he still has a plentiful staff of them under his employ, even if he is forced to pay their wages himself. I still have nightmares about the time he attached them to my arm when I was a child. Eyeless, writhing, bloodsucking monstrous worms! I remember watching them swell before my very eyes as he attached them one by one, as methodically as old Jofrey used to plant his tulip bulbs, on the underside of my arm. Father was forced to hold me down as they lined up on the vein like creditors. No amount of mama’s soothing could contain my screams as I tried to wriggle – agh! Even the word gives me shivers! – out of father’s grip until his arm ended up encircling my neck and I passed out. From the hysteria or his excessive restraint, I don’t know. Fortunately, when I came back to myself, the nasty squirming beasts were gone and my arm bandaged to hide all signs of their connection to me.

While we were in Kollam, I developed a bright red rash on the very same spot. The medic speculated that it was from the heat, but I knew its true origin. It has reappeared many times in the intervening years, and the heat has nothing to do with it.

There is great excitement here as preparation for our expedition proceeds at a devilish speed. I am not letting the recent sputter of negative froth deter me in the least. Villiers, our crew chief, is a man who has marched Canute-like against the prevailing tides of opinion many times in the past. Old Haliburton was one of the first to cast aspersions on V’s great zoological find from his Himalayan expedition, labelling the Yeti child little more than a “decapitated orangutan grafted poorly onto the torso of a bleached mountain gorilla.” The boor! The fact that the specimen was subsequently lost in transit reflects far more poorly on the Royal Mail than it does on my highly esteemed colleague. Many other, far more learned men had a chance to observe the specimen from relatively close quarters during the (frequently sold out) public exhibition and were completely unable to explain its origins, which speaks greater volume to its veracity than any oratorio of invective from a puffed-up failure like old Connie.

I don’t need to tell you the level of excitement that has been aroused by our discovery of the Yedra Scrolls, for word of them has spread not just to the edges of our shores but to every corner of the earth. I don’t wish to say too much about my progress, but I am very close to translating three of the five and believe the location of Piotrsgete will be revealed almost any day now. Part of the torrent of abuse heaped upon my head is coming from those who would like to examine the scrolls for themselves. They accuse me of (at best) self-interest and (at worst) of outright fraud. Empty barrels, all of them. All they want is a share of the glory for themselves, as if they had done anything to earn it other than scream at a friendly muckraker. I have seen it all before. “Let them chatter,” says Villiers. It will mean nothing when we return with the key to the greatest mystery in the history of humankind! I do admire his enthusiasm, even when I can’t always entirely grasp every word of his speech. In truth, I have never been able to fully ascertain if he is French or Spanish or Italian (his background contains, I believe, a bit of all three). As you know, I have never agreed with auntie Mame in her belief that human breeding is solely indicative of future character, as if we were nothing more than dachshunds. You could ask for no better illustration of that principle than uncle Harold. Being grandnephew of the earl of Somerset certainly didn’t seem to stop him from presenting his organ to all and sundry in the middle of cousin William’s wedding reception. And that was before old age supposedly robbed him of his keener reasoning. I believe he is better off in the Westphalia, even if he does on occasion escape the grounds and run to the police with fanciful stories of kidnapping and torture. I’m sure the Shropshire constabulary has heard many such tall tales over the years and has long since stopped giving them any credence.

I hope Elspeth is progressing well with her studies and has not given you any more trouble since the summer. The anniversary is always the time she seems to feel the loss of her mother most keenly. Being a Smythe, of course, she is far too stubborn to express her feelings in any conventional manner. You would no doubt say that it is my fault, but Elly is more like her mother than she will ever understand. Young Ronnie Fisher could make a study of her if he’s looking for any more proof of Mendel’s laws, but I wouldn’t wish her wrath on the poor chap.

It pains me to be unable to follow her studies more closely. Tellier says he has never seen a more promising mathematical brain. If only she would apply it more regularly to mathematics! My expeditions have far too often taken me away. I know you will laugh when I say this, but this is going to be the last. I can think of no grander discovery with which to cap my career (resurrect it, some might say). And the hard truth of the matter is that I just don’t have the fortitude to march to the ends of the earth that I did when I was a young fool in my twenties.

I wish I had time to write more, Pip, and I will. Give my love to Elly, if she will have it. Give my best to Bertie. A hernia may seem like a simple operation, but it takes a man time to recover from such things.

Love,

T

∅

13th December 1922

St. Edward Hotel, London

Dearest Pip,

A breakthrough!

Hudson has released an early draft of his geological study of Greenland for review and Villiers has managed to purloin a copy on my behalf. It is much more difficult for me to obtain such material since I am no longer on the expeditionary committee (something old Haliburton was instrumental in engineering after my return from India, I have no doubt). The ink is barely dry on the pages, but it is already causing a storm of excitement within the Society. All who touch it must sign an oath of secrecy, which is most unusual. It was something of a risk for Reginald to pass it to me, particularly in light of the drubbing my reputation has taken of late, but he has not forgotten how enthusiastically I championed his Antarctic project in ’15, when many others were opposed. Loyalty is rare, but not yet as extinct as Edwards’ Dodo, I am happy to say.

Hudson apparently spent nearly five years wandering the frozen wastes – so long that I think many of us thought he had met the same fate as poor old Scott. He went there only a few years after Peary had been darting about trying to see if the place was attached to the pole (it is not, it seems). What he has found is, quite simply, nothing less than a revelation in the truest sense.

Greenland is, it appears, not one island, but three. Based on his drilling samples, Hudson has been able to determine that there are two outer islands (north and south islands, he calls them) that make up the coast and a third island beneath the ice sheet that covers most of the interior. Hudson spent much of his time sampling and mapping the centre island, which seems to have interested him most particularly.

With good reason.

Before I go any further, dear Pip, I must ask that you speak not a word of what I am about to tell you to any other living soul. Not to Elspeth or Carstairs, or especially mother, who would, I fear, become the most hysterical of all. I know this seems a trifle extreme, but once I have made it clear how this connects to my own research, I believe you will understand.

Based on Boltwood’s latest radiometric dating technique and careful analysis of his samples, Hudson has determined that the rock of the central island is less than 7,000 years old, which makes it several million years younger than the soil of its closest neighbours. Furthermore, it seems that if one were strolling around on that central island at that time, one would have found the climate to be as lush and warm as Tahiti is today. Hudson has found samplings of animals, plants and all manner of other species no scientific practitioner worth his salt would ever in his most remote imaginings have ever associated with the place. Snakes.

Tropical birds. Lizards.

And – most controversial of all – a variant of our very own homo sapiens.

Now, the fact that there were humans on Greenland is not an eyebrow raiser in and of itself, of course, but the fact that they were not of Paleo-Eskimo origin and were there almost three thousand years before we know of any evidence for the first humans in that place most certainly is.

Villiers tells me that reaction to Hudson’s paper has been decidedly mixed, if you can consider a combination of horror, embarrassment, shock and disbelief to be a mix. There are whispers growing louder every day that Hudson is simply mad, that he lost his mind by spending too much time in the frozen wastes climbing glaciers and drilling thousands of holes in the ground. By all accounts, he certainly does not look like a madman, though. I have not laid eyes on him myself, but Villiers tells me that Hudson does not look like a man who just spent ten years crawling over an ice floe. Men who are lucky enough to return from such expeditions usually do so in a state of frostbitten emaciation, short a finger or an ear or a nose (poor Gladstone – to this day, he still wears an ill-fitting prosthesis that makes him look like a drunken stork), worn to the bone and sporting haggard beards and haunted eyes. Such places seep into the marrow, altering forever not just a man’s appearance but his very soul, hollowing out the fire and replacing it with ice and wind. Many look like they have returned from the dead, but not by much of a margin. Hollow wasteland scarecrows, come back to frighten the living away from their particular patch of riches.

Hudson, by all accounts, is bouncing around London with the look and energy of a teenage boy, which is a rare behaviour for a man of almost 64. Villiers has seen him and swears that the transformation is both genuine and almost supernaturally eerie.

“He doesn’t just look younger, Tristan,” he whispered to me when handing over the pages. “I swear the man is younger. I was meeting the man I had always pictured in my head based on a photograph taken of him at the 1887 ceremony where he was named a Fellow. The man I shook hands with matched that photograph in every detail.”

The Apocalypse Club

The Apocalypse Club